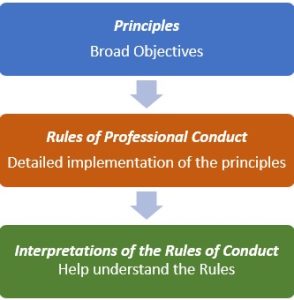

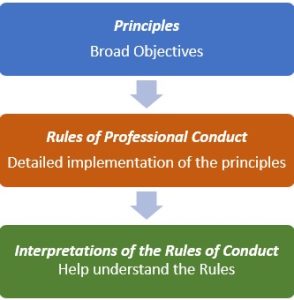

The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) is the largest professional association of accountants, with over 400,000 members in 145 countries. The AICPA has developed the “AICPA Code of Professional Conduct” which has become the foundation for most professional codes developed by regulatory agencies (including the California Board of Accountancy). The Code of Professional Conduct is built on the following hierarchy:

On December 15, 2014, a new codified version of The AICPA Code of Professional Conduct became effective. The new codified version brought together the principles, rules, and interpretations into a single document, organized by topic. Most of the philosophy of the prior Code continued into the new codified version, but the Code has always been a living document subject to change as needed. By organizing the Code by topic, users can more easily research and resolve their ethical questions. Each topic is presented as a series of threats and safeguards. Various threats that would undermine the CPA’s compliance with the Code are presented, followed by safeguards that might mitigate the threat.

Principles – The principles provide general objectives and a broad foundation for the more detailed rules. These basic principles are essentially values, or fundamental beliefs. If the detailed rules and interpretations do not provide sufficient guidance, the CPA can always test their ethical dilemma against the principles

Rules of Professional Conduct – The rules are the detailed implementation of the principles. These rules are the core of the Code of Professional Conduct and all members or the AICPA must follow them.

Interpretations of the Rules of Conduct are slightly less authoritative. Interpretations are intended to provide a better explanation of the rules. Members should comply with the interpretations; failure to do so places the burden on the CPA to justify why they did not comply with the interpretation. Under the prior Code of Professional Conduct, the AICPA also provided “ethics rulings.” These prior ethics rulings have been combined with interpretations.

The AICPA has adopted the following six Principles as the foundation of the Code of Conduct: [1]

Comments

Responsibilities –Sometimes people will often comply with laws, rules, policies, etc. and assume they have fulfilled their obligations, without any moral analysis. The outcome may not be optimal. The principle of “responsibilities” makes it clear that this moral analysis is essential for accountants.

Public Interest – Even though a CPA is paid by the client for an audit, the CPA is issuing a financial statement opinion for the benefit for the public. This includes anyone who uses the financial statements to make investment decisions, and those who use the information for analysis. The CPA must always remember that our profession relies on the public trust.

Integrity – Definitions for integrity include honesty, adherence to moral principles, unimpaired virtue, and honor. The information and advice given by accountants require integrity, otherwise that information and advice is of little value.

Objectivity and Independence – To be independent “in fact” means by all typical measures. However, there are some times that an accountant meets the requirements for independence, but the circumstances might cause other people to doubt the accountant’s independence.

Due Care – There are three components of due care, which basically ask that you (1) do your best, (2) strive to increase your skills, and (3) follow all of the accounting, auditing, and ethical standards.

Scope and Nature of Services – this principle basically states that when accepting new clients, engagements, or tasks you should consider the first five principles and only accept the new work if you can comply with all of the principles.

The reorganized Code of Professional Conduct is structured into four main sections:

The Preface is an introductory section that includes:

Part 1 is by far the largest section of the Code, comprising over 100 pages. This part applies to CPAs who work in “public practice” which basically means they work for a CPA firm. CPA firms often provide “attest” services, which are services to independently audit or review financial statements. Since other people may rely on the CPA’s audit or review, it is essential that the CPA firm and its employees be independent from the client company. Independence is therefore a significant component of part 1 of the Code. Sections in part 1 include:

Each of these rules begins with the related rules, and then adds the corresponding interpretations and to help better understand the rule. To better understand the rules as they apply to members in public practice, the rules are listed below.

The first section of part 1 is the introduction. This section establishes the conceptual framework and provides a methodology for resolving ethical conflicts.

The conceptual framework provides that CPAs should identify the threats that might impair their ability to comply with the Code. The Code states that many threats can be divided into seven categories:

Seven Categories of Threats

After identifying the threat, the CPA should evaluate the significance of the threat, and then consider safeguards that can eliminate the threat or reduce it to an acceptable level. There are three basic categories of safeguards:

The introductory section concludes with a methodology to resolve ethical conflicts. The process is as follows:

Rule: In the performance of any professional service, a member shall maintain objectivity and integrity, shall be free of conflicts of interest, and shall not knowingly misrepresent facts or subordinate his or her judgment to others.

Integrity and objectivity apply to accountants in any position or for any service provided. Accountants provide information to management, investors, creditors, regulatory and tax agencies, and other stakeholders. In order for the information to be useful, it must be trustworthy. The information is trustworthy only if the accountant producing the information has integrity and objectivity.

Rule: A member in public practice shall be independent in the performance of professional services as required by standards promulgated by bodies designated by Council.

Independence is a core value for financial statement auditors. Auditors should have an independent mental attitude and should also be independent in appearance. By applying professional skepticism in their audit tasks and providing an independent opinion on financial statements, investors and creditors can rely on the financial statements. The auditor’s independent opinion is an essential element in smoothly functioning capital markets.

Rule: A member shall comply with the following standards and with any interpretations thereof by bodies designated by Council.

You may recognize these “general standards” as some of the auditing standards, originally adopted by the AICPA and later by the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB).

Rule: A member who performs auditing, review, compilation, management consulting, tax, or other professional services shall comply with standards promulgated by bodies designated by Council.

The standards-setting bodies approved by AICPA for this Rule include the following:

Rule: A member shall not (1) express an opinion or state affirmatively that the financial statements or other financial data of any entity are presented in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles or (2) state that he or she is not aware of any material modifications that should be made to such statements or data in order for them to be in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles, if such statements or data contain any departure from an accounting principle promulgated by bodies designated by Council to establish such principles that has a material effect on the statements or data taken as a whole. If, however, the statements or data contain such a departure and the member can demonstrate that due to unusual circumstances the financial statements or data would otherwise have been misleading, the member can comply with the rule by describing the departure, its approximate effects, if practicable, and the reasons why compliance with the principle would result in a misleading statement.

This rule essentially recognizes the authoritative bodies that create Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), requires that auditors correctly incorporate a reference to GAAP in their audit opinions, and gives the AICPA jurisdiction for discipline of a member (which would be in addition to any discipline from other authorities.)

Rule: A member shall not commit an act discreditable to the profession.

This is a very brief rule and general rule, which allows a broad range of professional and personal actions to be determined to be discreditable. The interpretations to the rule provide some guidance on the types of acts that are discreditable, including:

These are the acts specified in interpretations to rule on “acts discreditable.” Other acts may also be discreditable. CPAs should evaluate their responsibility to the reputation of the profession when making professional and personal choices.

The AICPA’s Website identifies all CPAs that have been disciplined

Rule on Contingent Fees: A member in public practice shall not

(1) Perform for a contingent fee any professional services for, or receive such a fee from a client for whom the member or the member’s firm performs,

(a) an audit or review of a financial statement; or

(b) a compilation of a financial statement when the member expects, or reasonably might expect, that a third party will use the financial statement and the member’s compilation report does not disclose a lack of independence; or

(c) an examination of prospective financial information; or

(2) Prepare an original or amended tax return or claim for a tax refund for a contingent fee for any client.

The prohibition in (1) above applies during the period in which the member or the member’s firm is engaged to perform any of the services listed above and the period covered by any historical financial statements involved in any such listed services.

Except as stated in the next sentence, a contingent fee is a fee established for the performance of any service pursuant to an arrangement in which no fee will be charged unless a specified finding or result is attained, or in which the amount of the fee is otherwise dependent upon the finding or result of such service. Solely for purposes of this rule, fees are not regarded as being contingent if fixed by courts or other public authorities, or, in tax matters, if determined based on the results of judicial proceedings or the findings of governmental agencies.

A member’s fees may vary depending, for example, on the complexity of services rendered.

Contingent fees are based on an outcome. For example, personal injury attorneys often charge a percentage of the final damage award. If they do not obtain money for their client, they do not get paid. This gives the attorney a vested interest in the case outcome. There is no expectation that the attorney is independent or objective. For many services performed by CPAs, independence and objectivity are essential. To maintain their independence and objectivity, the contingent fees rule prohibits charging contingent fees for specified types of services.

Rule on Commissions and Referral Fees

A. Prohibited commissions

A member in public practice shall not for a commission recommend or refer to a client any product or service, or for a commission recommend or refer any product or service to be supplied by a client, or receive a commission, when the member or the member’s firm also performs for that client

(a) an audit or review of a financial statement; or

(b) a compilation of a financial statement when the member expects, or reasonably might expect, that a third party will use the financial statement and the member’s compilation report does not disclose a lack of independence; or

(c) an examination of prospective financial information.

This prohibition applies during the period in which the member is engaged to perform any of the services listed above and the period covered by any historical financial statements involved in such listed services.

B. Disclosure of permitted commissions

A member in public practice who is not prohibited by this rule from performing services for or receiving a commission and who is paid or expects to be paid a commission shall disclose that fact to any person or entity to whom the member recommends or refers a product or service to which the commission relates.

Any member who accepts a referral fee for recommending or referring any service of a CPA to any person or entity or who pays a referral fee to obtain a client shall disclose such acceptance or payment to the client.

This rule is in support of the rules on independence, integrity, and objectivity. Clients ask for advice or referrals from their accountant as a trusted professional. In order for that advice to be trustworthy, the accountant’s integrity and objectivity must be beyond reproach. Avoiding commissions and referral fees provides auditors with greater independence and objectivity, both in fact and in appearance. In those circumstances where a CPA can accept a commission or referral fee, being open and honest with the client exhibits integrity and allows the client to make their own judgments about any conflicts that may affect the CPA’s objectivity.

Rule: A member in public practice shall not seek to obtain clients by advertising or other forms of solicitation in a manner that is false, misleading, or deceptive. Solicitation by the use of coercion, over-reaching, or harassing conduct is prohibited.

Historically, CPAs were prohibited by the AICPA from advertising. After the Federal Fair Trade Commission questioned this as a restraint of trade, the Code of Conduct was amended to allow advertising. This rule allows CPAs to advertise, but the advertising must not be false, misleading, or deceptive. The interpretations of rule 502 define what it means for advertising to be false, misleading, or deceptive. The interpretations also hold the CPA responsible for the advertising of any third-party that advertises to obtain clients on behalf of the CPA.

Rule: A member in public practice shall not disclose any confidential client information without the specific consent of the client.

This rule shall not be construed (1) to relieve a member of his or her professional obligations of the “Compliance With Standards Rule” [1.310.001] or the “Accounting Principles Rule” [1.320.001], (2) to affect in any way the member’s obligation to comply with a validly issued and enforceable subpoena or summons, or to prohibit a member’s compliance with applicable laws and government regulations, (3) to prohibit review of a member’s professional practice under AICPA or state CPA society or Board of Accountancy authorization, or (4) to preclude a member from initiating a complaint with, or responding to any inquiry made by, the professional ethics division or trial board of the Institute or a duly constituted investigative or disciplinary body of a state CPA society or Board of Accountancy. Members of any of the bodies identified in (4) above and members involved with professional practice reviews identified in (3) above shall not use to their own advantage or disclose any member’s confidential client information that comes to their attention in carrying out those activities. This prohibition shall not restrict members’ exchange of information in connection with the investigative or disciplinary proceedings described in (4) above or the professional practice reviews described in (3) above.

Independent accountants/auditors often have access to highly sensitive client information. This rule establishes that independent accountants owe a high degree of confidentiality to their clients. To breach that confidentiality would be a breach of ethics. This rule prohibits auditors from disclosing illegal acts, unless there is a legal requirement to do so. One exception in law is that the auditor is required to report an illegal act if the act is material to the financial statements to the point that the auditors will need to modify their opinion on the financial statements, and the client management and board of directors has not taken action to correct the problem.

A member may practice public accounting only in a form of organization permitted by law or regulation whose characteristics conform to resolutions of Council.

A member shall not practice public accounting under a firm name that is misleading.

Names of one or more past owners may be included in the firm name of a successor organization.

A firm may not designate itself as “Members of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants” unless all of its CPA owners are members of the Institute.

You may have noticed that all CPA firms have names in them, and you never see a name such as “Fabulous CPAs” (unless one of the CPAs happened to have the last name of Fabulous).

Many of the provisions that apply to CPAs in public practice also apply to CPAs in business (industry or government). The most significant difference is that the independence rules do not apply to members in business. That is because an employee cannot be independent of their employer, nor is there any need for them to be independent. Employees are expected to be loyal to their employer, not independent. The following parts of the Code that apply to members in public accounting also apply to members in business:

Part 3 of the Code is the shortest of the three major sections of the AICPA Code of Professional Conduct. Part 1 applies to members in public accounting, and part 2 applies to members in business (industry or government). Part 3 applies to other members who are neither employed in public accounting nor in business. This primarily applies to CPAs who are not currently working because they are between jobs or retired. The same acts that are listed as discreditable to CPAs in public accounting or business are also listed for other members.

On January 28, 2014, the new codified AICPA Code of Professional Conduct was adopted by the AICPA’s Professional Ethics Executive Committee (PEEC). Most parts of the new Code of Professional Conduct became effective on December 15, 2014. The conceptual frameworks and some sections are effective December 15, 2015, but earlier adoption is encouraged. The AICPA has released and online format of the new Code, making it easy for users to click through a number of links and easily access the specific guidance they are seeking. The AICPA occasionally makes additions, changes, and deletions to the Code. We can expect future changes as our society and the accounting profession continue to evolve.

The AICPA Code of Conduct applies only to members of the AICPA. Membership in the AICPA is voluntary. Some CPAs may belong to other professional organizations, while others may choose not to belong to any organizations.

Although the AICPA Code of Conduct applies only to AICPA members, the Code has been used by all state boards of accountancy in creating their own state laws and regulations. As a result, all CPAs must follow the code of conduct or face potential disciplinary action in their state. Although the AICPA has provided many interpretations to assist CPAs in making ethical decisions, the CPA should always consider the spirit of the principles and include a moral analysis of their choices. The Principles in the Code of Conduct should be incorporated into the professional’s character as virtues.

Questions for Research and Discussion

1. Why does the accounting profession need a code of conduct?

2. What are the components of the AICPA Code of Conduct?

3. Compare and contrast the Principles and the Rules.

4. Compare and contrast the virtues of independence, objectivity, and integrity.

5. What would the effects be on the capital markets if investors did not perceive financial statement auditors as having independence, objectivity, and integrity?

6. Who creates Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP)?

7. What is the primary difference between parts 1 and 2 of the AICPA Code of Professional Conduct?

8. If a CPA were required by a subpoena or court order to produce confidential client documents, would compliance with the legal demand constitute a violation of the Code of Conduct?

9. If a CPA anticipated that their work might be subject to court order or subpoena, can you think of a way to protect that work with attorney-client privilege?

10. If a CPA provided consulting services to help a client reduce their energy usage, would it be permissible for a CPA to charge a contingent fee of 5% of any cost savings?

11. If a CPA provided expert witness testimony on behalf of a plaintiff, could the CPA charge a contingent fee that is 5% of any jury award?

12. Visit the list of disciplinary actions for violations of the AICPA Code. Choose the current year and select one disciplinary case.

A problem or situation that requires a person or organization to choose between alternatives that must be evaluated as right (ethical) or wrong (unethical).

Read more: http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/ethical-issue.html

× Close definitionan expression of intention to inflict evil, injury, or damage

× Close definitiona precautionary measure