Over 2 million + professionals use CFI to learn accounting, financial analysis, modeling and more. Unlock the essentials of corporate finance with our free resources and get an exclusive sneak peek at the first module of each course. Start Free

A Letter of Credit (LC) can be thought of as a guarantee that is backstopped by the Financial Institution that issues it. One party is required to guarantee something to another party; typically, it’s payment, but not always – it could also be guaranteeing that some project will be completed.

Because counterparties in many transactions are (relatively) unknown to one another, it’s common for one party to demonstrate its creditworthiness by tapping into its primary banking relationship and asking that bank to issue an LC on its behalf.

That counterparty can then get comfortable with a transaction knowing that the buyer’s bank has issued a guarantee. In exchange for a fee, the buyer is effectively substituting its own creditworthiness (which is hard for the seller to measure) with that of a large and reputable financial institution.

Letters of Credit are especially common for cross-border transactions where trust and timing issues are exacerbated by other factors like political and shipping risk, as well as limitations around security registration.

Letters of Credit fall into one of two categories. They are either financial in nature or documentary (sometimes called a Standby LC).

Financial LCs guarantee payment and can be thought of as a certified cheque in retail banking; once certain transaction terms have been met (like a bill of lading presented to indicate shipment of goods), the LC is redeemed in exchange for immediate payment. Financial LCs are intended as a method of payment, albeit one managed and overseen by financial institutions instead of the individual trading partners.

Documentary (or Standby) LCs also serve as a guarantee of payment; however, they are not issued with an expectation that they will be redeemed. If one is, it means that something likely went wrong with the transaction or with the contract terms. Standby LCs are designed to “stand by” in the event that some transaction terms are not met.

Let’s assume there are two parties involved in a transaction – a buyer and a seller. The seller wants some guarantee of payment from the buyer before agreeing to contract terms. Buyer’s management approaches the Loan Officer at their Commercial Bank to get an LC.

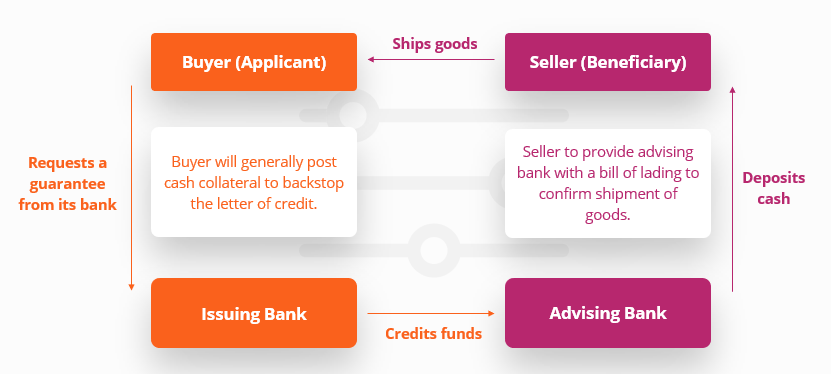

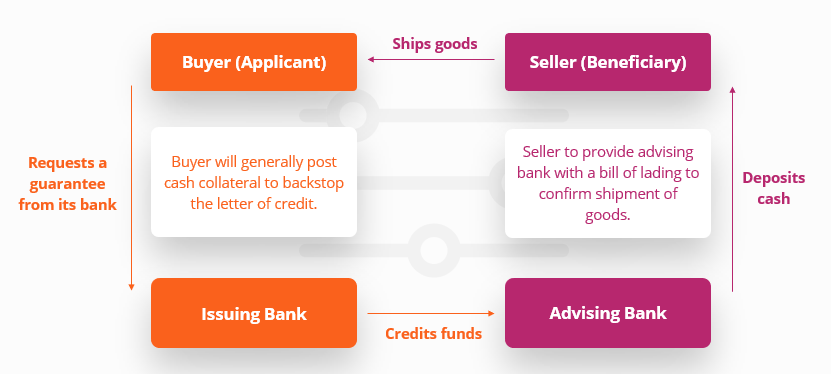

In this example transaction, the buyer is also called the Applicant. The Applicant’s financial institution is called the Issuing Bank since it will be issuing the trade instrument on behalf of its client (the applicant). The seller, in this case, is the Beneficiary (meaning they will benefit from the proceeds of the guarantee when it is called). Given that the seller is unlikely an expert in Trade Finance instruments (like LCs), its own bank, in this case, the Advising Bank will serve as an intermediary.

Assume the terms of the transaction are that payment shall be made upon shipment of physical goods. The seller will present its bank (the Advising Bank) with a bill of lading once the shipment has been confirmed. The Advising Bank will then contact the Issuing Bank to call (or redeem) the financial LC; they, in turn, will credit funds to the Advising Bank by way of some international payment network (such as SWIFT), who in turn will deposit cash into its client (the seller’s) account.

Since the Issuing Bank is required to actually remit payment when the LC is called, they need to have something highly liquid available. As a result, the applicant will generally either post cash collateral to backstop the LC, or management may be able to “carve out” a portion of its operating line of credit instead.

Unlike a Financial LC, Standby LCs are issued to provide comfort to the beneficiary that payment will be forthcoming if some terms of a contract between the beneficiary and the applicant are not met.

A common use case for a Standby LC is in commercial real estate. A prospective tenant, call them Party A (the Applicant), is looking to sign a 5-year lease with Party B (the landlord and beneficiary) for a 100,000-square-foot warehouse facility.

Assume that the facility will require some modest customization. The landlord wants to know that, should they spend the money to do these renovations, Party A won’t default on its rent and leave them with a large facility that’s already been renovated to suit a specific tenant’s needs.

Party B might ask Party A for a Standby Letter of Credit in the amount of 12, 18, or perhaps even 24 months’ rent to protect its financial interest in the property. Should party A default on its rent payments, Party B would go to its own bank (the Advising Bank) and declare that the contract terms were breached. The Advising bank would notify the Issuing Bank, which would immediately remit payment on behalf of the Applicant (its client).

Like a Financial Letter of Credit, the Issuing Bank needs funds available immediately if the LC gets called. In this case, Standby LCs are similar in that they too often require some kind of highly liquid collateral, such as cash or a “carve out” from the borrower’s operating line of credit.

Credit analysts looking to assess the creditworthiness of an LC applicant will approach their due diligence using many of the same criteria and risk models that they would for a borrower seeking any other type of Commercial Lending. Having said that, there are two fairly unique factors:

Thank you for reading CFI’s guide to Letter of Credit. To keep advancing your career, the additional CFI resources below will be useful:

Stand out and gain a competitive edge as a commercial banker, loan officer or credit analyst with advanced knowledge, real-world analysis skills, and career confidence.